The Red Sea sanctioned ships story is a paradox of resilience and opacity. While mainstream carriers rerouted around Africa amid Houthi attacks, portions of the Russia-linked “shadow fleet” continued to use Suez/Bab el-Mandeb, aided by flag-hopping, rapid name changes and unconventional insurance arrangements. Recent research shows how targeting errors, shifting registries (including Djibouti), and expanding Western sanctions intersected with operational choices by sanctioned tankers moving Russian oil to India and China.

Context / Background

Since late 2023, Houthi strikes and threats in the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have reshaped commercial risk. Yet tankers carrying Russian crude often kept transiting Suez in 2024, even as other trades diverted via the Cape. Market intelligence firm Kpler assessed that Russian crude flows through the canal remained broadly stable, with roughly around 55% of Russia’s crude exports still using Suez in 2024 an outlier compared to other cargoes.

This persistence coincided with a sanctions environment that pressured Russia-linked maritime networks while also expanding the global pool of older, lower-transparency tankers. Western authorities escalated measures through 2024–2025 London in particular rolled out successive designations focusing on vessels, owners and facilitators associated with the “shadow fleet.”

Key Developments or Current Situation

Targeting errors and continued transits. The Washington Institute documented multiple cases in which Houthis struck or attempted to strike Russia-linked tankers based on outdated ownership or registry data yet those ships resumed Red Sea voyages afterward, suggesting that the perceived risk did not permanently deter them from Suez/Bab el-Mandeb. Notably, Blue Lagoon I resumed transits in January 2025 with AIS broadcasting after being targeted more than once in September 2024.

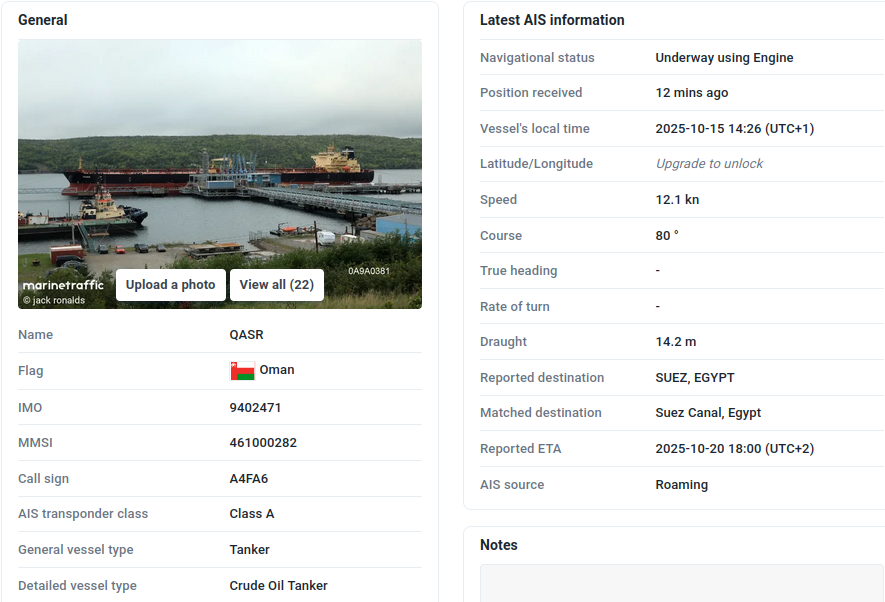

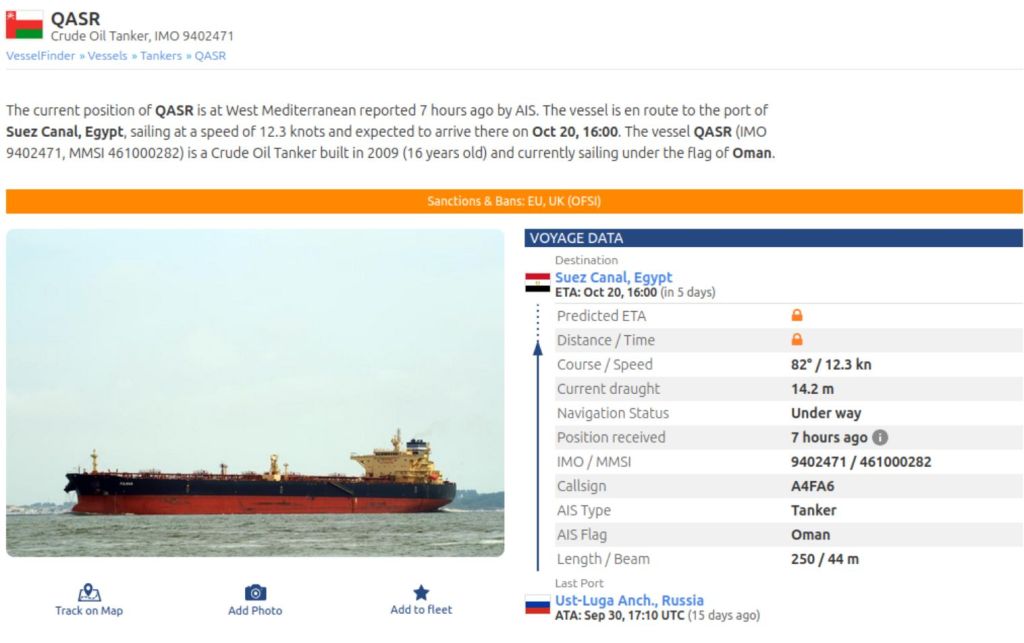

Apar (ex-Andromeda Star / Feng Shou). EU-sanctioned and later Djibouti-flagged, Apar (IMO 9402471) drew attention after a March 2024 collision in the Danish Straits amid reports the ship presented invalid insurance documents. It then came under Houthi fire in April 2024 while carrying crude toward India and broadcasting a neutrality message. The tanker shuttled Russian oil to India and China multiple times over 2023–2024 and shifted names and flags in December 2024.

Lahar (ex-Sai Baba). Targeted in December 2023, later sanctioned by the UK in October 2024, and subsequently reflagged to Djibouti, Lahar (IMO 9321691) was last seen in the southern Red Sea in August 2024 before operating in Asian waters toward end-2024.

Flag hopping and the Djibouti registry. The same research and trade-press reporting indicate sanctioned or at-risk ships have at times adopted the Djibouti flag, with episodes of subsequent deflagging under scrutiny from authorities and registries. Analysts also note rapid post-sanctions reflagging to other open registries, underscoring regulatory arbitrage dynamics.

Sanctions widening in 2025. The UK announced large packages against shadow-fleet vessels through 2025, adding dozens of ships and entities, and signaling tighter enforcement. These moves followed earlier rounds in late 2024 and added compliance pressure on shipowners, insurers and service providers linked to Russian oil logistics.

Red Sea Sanctioned Ships: What the Crisis Revealed

1) A distinct risk calculus. Unlike liner operators or energy majors, sanctioned or high-risk tankers often operate outside mainstream insurance and classification ecosystems. The Andromeda Star/Apar case, where documents presented to authorities were not accepted as valid by the purported insurer, illustrates a vulnerability: liability cover may be opaque or disputed, yet voyages continue if charter economics and port access remain viable.

2) Data lags can shape targeting. Several Russia or China-linked ships were struck when attackers relied on stale registry/ownership information. When the same ships later transited without incident, it suggested the targeting matrix had shifted or that messaging (including AIS status notes) reduced their profile. For commercial risk managers, the episode underscored the premium on timely, verified vessel data—and the hazards of attribution amid frequent name/flag changes.

3) Shadow-fleet adaptation via name/flag changes. Rapid reflagging including to Djibouti and frequent renamings complicated compliance screening and maritime domain awareness. Trade reporting shows sanctioned vessels deflagged and then reappearing under new registries; authorities and registries periodically purge such ships, but the window between action and reflagging is often short.

4) Suez still mattered for Russian crude. Kpler’s assessment that Russian crude’s Suez share hovered near ~55% in 2024 while many other cargoes detoured highlights a striking continuity. For sanctioned trades, the time-distance advantage of Suez, plus destination markets in India and China, outweighed the elevated Houthi threat especially once targeting errors became evident and some ships signaled cargo origin or neutrality in AIS remarks.

5) Enforcement is broadening and may raise the cost of opacity. UK measures in late 2024 and through 2025 expanded to dozens of ships and associated networks, mirrored by allied efforts. Each tranche adds friction: more port bans, service denials, and due-diligence alerts for brokers and financiers. But enforcement has to keep pace with flag hopping and layered ownership structures.

Operational and Legal Implications

Insurance and liability exposure. Where International Group backed cover is absent or contested, collision, pollution and wreck-removal liabilities pose systemic risks to coastal states and straits dramatically illustrated by investigations after the Danish Straits incident. The possibility that a major casualty involves a vessel with questionable coverage concentrates attention on port-state control and canal authorities’ vetting.

Flag-state responsibility and registry governance. Episodes of Djibouti deflagging and subsequent reflagging elsewhere raise questions about registry oversight and coordination with sanctions lists. While some administrations have acted to remove designated tonnage, the latency between designation, deflagging and reflagging sustains a grey market in services, including surveys and certificates.

AIS and deceptive practices. Name/flag swaps, AIS status messages, and, in other contexts, alleged GNSS spoofing complicate surveillance. Compliance teams increasingly triangulate AIS, port data, and cargo intelligence; yet, as the Red Sea episode showed, even armed actors can misread data, with real-world consequences for crews and navigation safety.

Canal and chokepoint management. If sanctioned fleets keep using Suez while mainstream trades divert, risk externalities concentrate on critical passages and nearby SAR resources. Authorities balancing throughput with safety may intensify inspections, impose documentation checks, or cooperate with insurers and P&I correspondents to verify cover before transit. (This is a practical inference from reported incidents and sanctions enforcement trends.)

Commercial Consequences

Routing economics versus exposure. For sanctioned trades, the incremental cost of Cape rerouting can exceed perceived gains in safety; hence, continued Red Sea use even after attacks, provided that escorts, patrols, or changed targeting criteria lower the probability of incident. For compliant owners, by contrast, the cost of reputational, legal and insurance exposure argues for detours until risk normalizes—explaining the divergence in behavior across segments.

Compliance workload for the wider industry. Each new UK/EU/US action expands screening universes for banks, charterers and terminals. The rise of flag hopping shortens the shelf life of static watchlists and drives adoption of dynamic risk models that weight ownership webs, management switches, and historical port footprints workflows highlighted by maritime analytics providers after mid-2025 designations.

Egypt’s Suez exposure. If a subset of older, lightly insured ships keeps using the canal while high-value liner traffic diverts, incident risk skews toward assets least equipped to absorb losses. That asymmetry matters for Egypt’s revenue and safety posture a reminder that canal authorities’ screening and fee policy can indirectly shape the risk composition of traffic in crisis periods. (Analytical linkage based on the composition of users described above.)

Consequences / Perspectives

Safety of seafarers. Crews aboard sanctioned or high-risk ships shoulder disproportionate danger from mis-targeting to emergency response gaps if cover is disputed. The Red Sea episode reinforced IMO guidance on seafarer protection and best-practice transits, but enforcement asymmetries remain where opaque operators are involved.

What to watch.

- Registry behavior: whether Djibouti and other open registries tighten vetting, and how quickly deflagged ships reappear elsewhere. Lloyd’s List+1

- Sanctions cadence: the scale and specificity of new designations against vessels, owners, and facilitators; cumulative impact on service denial. Reuters+1

- Canal policy and inspections: any shifts in Suez transit requirements for higher-risk tonnage; cooperation with insurers and P&I. (Analytical inference based on the incidents and enforcement trendlines cited.) tradewindsnews.com

The Red Sea crisis, counter-intuitively, illuminated the sanctioned fleet’s operating model more than it deterred it. Name and flag changes, unconventional insurance, and opportunistic routing enabled continued trade even under attack—at the cost of transparency and safety externalities borne by crews and littoral states.