A balance disrupted by global warming

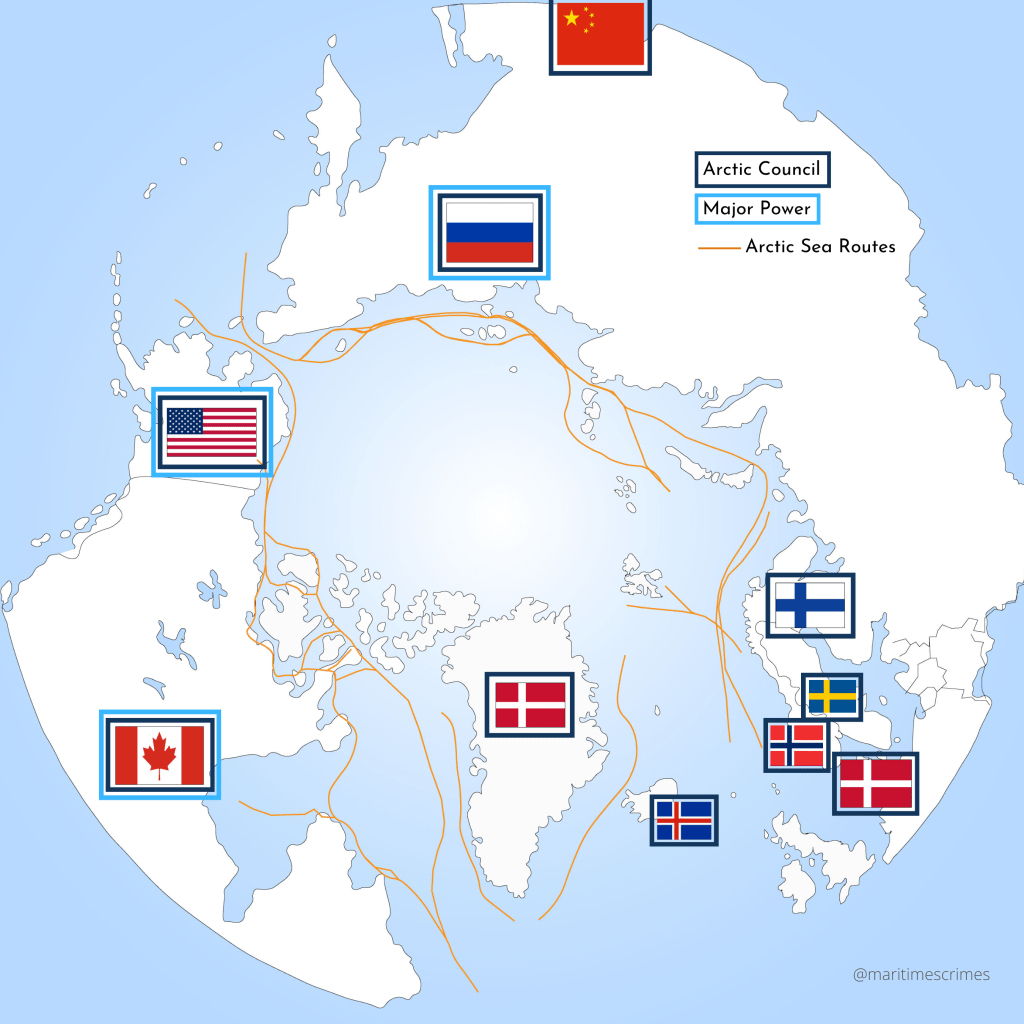

A polar region located north of 66°33N, the Arctic is the scene of renewed great power competition (GPC). This area is vital for Russia, which seeks to dominate it, and represents an opportunity for China, which has integrated it into a “Polar Belt and Road Initiative”. While the stakes are primarily economic, security and environmental, the maritime and defense implications are considerable. Attached to the freedom of navigation that guarantees their freedom of action, Danemark and Norway must develop their influence to protect their interests.

Warming in the Arctic is three to seven times greater than global averages, resulting in accelerated melting of the pack ice. In addition to the significant environmental consequences arising from the release of CO2 contained in the permafrost, speculation is focused on the economic prospects offered by access to thirty trillion dollars’ worth of mineral wealth. However, the exploitation of these resources and shipping routes will remain limited due to the extremely harsh climatic conditions, which impose very high operating costs.

A strategic area of avarice and threat

Nevertheless, Arctic competition will remain at the center of GPC. For Russia, the area represents 15% of its GDP, a fifth of its exports and the stronghold of its nuclear force. For China, with its sights set on increased global leadership, its presence is linked above all to a policy of power and influence, with massive financial and economic operations in bordering countries such as Canada, Greenland and Russia.

These issues increase the risk of tension at a time of uninhibited use of force. On the Russian side, the domination of this vital space relies on lawfare and military might. For example, under the authority of Rosatom, the administration of Arctic routes requires the presence of an ice pilot and the escort of a requested icebreaker with a fortnight’s notice, including for military vessels, which are required to give 45 days’ notice. The Russian parliament is even considering the possibility of denouncing the “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” so that Russia can claim its rights over the northern sea route, which it describes as “an artery of inland transport”.

Russia is also continuing to militarize the Far North to assert its sovereignty and develop A2AD capability. China’s military presence remains relatively weak, but will inevitably increase as it acquires new resources as part of the “Polar Belt and Road Initiative”. The shift of Chinese military forces to the Atlantic via the Arctic routes will soon generate a major imbalance of forces in the Atlantic, a stronghold considered to be in the hands of Western forces.

A role to play for Europe

Committed to freedom of navigation, Europe must react. Beyond the military aspect, some European countries are already major economic players in the Arctic and must protect their interests. For example, with over 200 companies at work in the area, France is the leading Arctic tourism operator with Ponant, a major energy and technical player with Total on the Yamal site, and an internationally recognized scientific player with the Paul-Emile Victor Polar Institute. As is Sweden, Europe’s leading iron producer, especially for Norrland. Around 88% of the EU’s iron resources come from the Barents Sea region. Sweden has the third largest fleet of icebreakers in the world, behind Russia and Canada. Sweden has six icebreakers, including a research and escort vessel.

The Arctic comprises a concentration of economic, security and environmental issues that give rise to significant maritime and military implications. Russia’s desire to dominate the region and China’s economic ambitions threaten the values upheld by Europe, which must protect its Arctic interests. Committed diplomacy with bordering countries, participation in reinsurance measures and continued operational deployment developing greater control of the zone constitute a realistic roadmap for these countries.