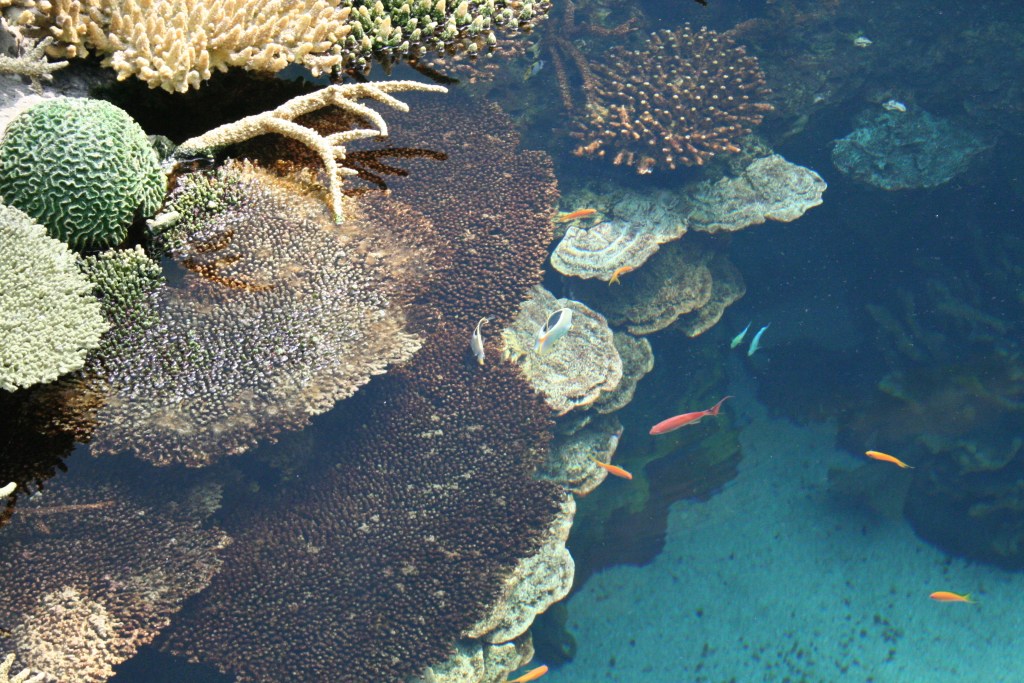

Coral reefs sit at the junction of climate physics and coastal livelihoods. Their colours and architectural complexity are built by a fragile symbiosis between corals and microscopic algae. When seas stay too hot for too long, that contract breaks. The years 2024–2025 marked an inflection: the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed on 15 April 2024 the fourth global mass bleaching event on record, driven by exceptional marine heatwaves across all basins (NOAA confirmation). By September 2025, NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch estimated that bleaching-level heat stress had affected about 84 % of the world’s reef area since January 2023 (Coral Reef Watch status). In October 2025, a synthesis by more than 160 scientists warned that warm‑water coral reefs are the first ecosystem to have crossed a planetary tipping point, with widespread mortality already underway (Global Tipping Points Report 2025; see also CNRS interview with Serge Planes).

From marine heatwaves to mass bleaching: what 2024–2025 changed

Marine heatwaves—periods of unusually high sea‑surface temperatures lasting days to months—have become more frequent, longer and more intense, stacking heat stress across seasons. For many tropical coral taxa, sustained temperatures of roughly 30–31 °C mark the upper limit of thermal tolerance. Beyond this, the risk of bleaching rises rapidly. NOAA and the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) characterised 2023–2025 as a basin‑spanning event, with documented bleaching in at least 83 countries and territories (ICRI–NOAA joint note). This episode follows mass events in 1998, 2010 and 2014–2017, but stands out for its global synchrony and recurrence; in several regions, severe bleaching has occurred in consecutive years, leaving little recovery time (Reuters on NOAA declaration).

Bleaching is not mortality per se; it is the loss of symbiotic algae (dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae) that normally supply most of the coral’s energy through photosynthesis. If thermal stress eases within weeks and local water quality is high, many colonies can regain symbionts and survive. But the frequency and cumulative intensity of heat stress now shorten recovery windows, opening the door to starvation, disease and partial or total colony death (peer‑reviewed synthesis on the fourth event).

Physiology of collapse: when symbiosis breaks

The coral–algae partnership

Hermatypic (reef‑building) corals live in mutualism with intracellular algae. In clear, oligotrophic tropical waters—typically low in nutrients—the algae’s photosynthates can meet up to 90 % of the host’s energetic needs, enabling rapid calcification and the construction of three‑dimensional reef frameworks. Thermal anomalies disrupt this efficiency. High temperatures combined with strong light drive the algal photosystems into oxidative stress, producing reactive oxygen species that damage both partners. To protect itself, the coral expels the algae, becoming pale or white as the pigmented symbionts vanish (CNRS interview).

Energy debt, disease risk and mortality

Once bleached, corals face an energy deficit. They can increase heterotrophic feeding (plankton capture) and draw down lipid reserves, but only for a limited time. Prolonged heat leaves corals vulnerable to pathogens and bioeroders, and reduces reproductive output. If Degree Heating Weeks a cumulative metric of heat stress—reach critical thresholds over successive seasons, mortality escalates. Regional bulletins in late 2025 still showed elevated alerts in parts of the Middle East and western Indian Ocean following extreme summer anomalies (NOAA alert maps, Oct 2025).

A non‑uniform crisis: regional winners, losers and lags

Severe decline zones

Evidence points to marked declines in sections of the Caribbean, the Persian/Arabian Gulf, and portions of the Red Sea and western Indian Ocean, where compound stressors—very high summer maxima, low flushing, nutrient inputs and disease coincide. Shallow, enclosed lagoons and turbid near port areas have proven especially exposed. Reports from 2024–2025 documented extensive bleaching and mortality on popular tourism and fishing reefs, with socio‑economic effects that will be felt for years (global crisis update; AP overview).

Mixed signals and refugia

By contrast, parts of Southeast Asia and the Pacific show heterogeneous responses. Depth gradients, upwelling shadows, internal waves and turbid‑water assemblages create micro‑refugia where peak temperatures are blunted or light is attenuated. Thermal histories also matter: some Gulf corals acclimatise to summers above 34 °C but are near physiological limits; other assemblages with diverse symbiont types appear to tolerate transient spikes better. These contrasts echo scientist Serge Planes’s caution against declaring a uniform global state: some provinces may not yet have crossed a local tipping threshold, even as others clearly have (CNRS interview).

Why outcomes differ

Outcomes reflect the interaction of climate forcing with local stressors and management. Reefs with good water quality, lower fishing pressure and effective protection tend to bleach less severely and recover faster. Conversely, reefs near river mouths, untreated sewage outfalls, dredging sites or heavy anchorages experience additive stress higher turbidity, hypoxia, disease vectors that cut survival odds. The 2025 tipping‑points assessment underscores that while global warming sets the stage, local governance still shifts the trajectory (Global Tipping Points Report 2025; ICRI–NOAA).

Compounding pressures beyond climate

Wastewater and nutrient runoff. Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from untreated sewage and agricultural runoff fuel algal blooms and microbial activity that deprive corals of light and oxygen, and can intensify disease. Improving near‑shore water quality is among the fastest levers within reach of coastal authorities (CNRS interview).

Sediment plumes. Land clearing, river engineering and coastal construction increase fine sediment loads that smother recruits and reduce photosynthesis. Timing dredging to cooler seasons and establishing turbidity thresholds near ports and tourism hubs can lower risk.

Fishing pressure and extraction. Overfishing removes herbivores that keep macroalgae in check; destructive practices (blast fishing, poisons) and coral extraction for construction or souvenirs directly remove structure. Seasonal closures and gear restrictions help rebuild functional guilds.

Shipping and tourism impacts. Ship groundings, anchor scarring and poorly sited moorings fragment frameworks; antifouling contaminants, oil spills and chronic fuel residues impose additional stress. Routing adjustments and reef‑safe mooring fields reduce mechanical damage.

Invasive and outbreak species. Outbreaks of crown‑of‑thorns starfish (Acanthaster spp.) devastate coral cover; management programmes combining surveillance, targeted culls and nutrient controls have demonstrated benefits when sustained.

Evidence of resilience and realistic recovery timelines

Natural regeneration under reduced stress

Despite the severity of recent events, reefs retain remarkable regenerative capacity when stress abates. Field studies and monitoring after cyclones or localised bleaching show that coral cover and complexity can rebound within five to six years in well‑managed waters with strong larval supply an optimism echoed by Serge Planes, while stressing that recovery presumes no new major heat event in the interval (CNRS interview). The challenge is that return intervals for high Degree Heating Weeks are shortening; in many provinces, severe bleaching now recurs every two to five years, truncating the recovery window (Coral Reef Watch status).

Assisted resilience: what works and what does not

Marine protected areas (MPAs) improve fish biomass and ecosystem processes that stabilise reefs, but do not stop heat stress. Their value lies in buying time by reducing local pressures. Water quality controls secondary/tertiary sewage treatment, stormwater retention in urban catchments, erosion controls in agriculture have repeatedly shown quick ecological returns on near‑shore reefs. Early‑warning systems that translate heat‑stress forecasts into seasonal closures for tourism or fisheries can reduce incidental damage during peak vulnerability (NOAA Coral Reef Watch tools).

Active restoration (nurseries, outplanting) yields local benefits in high value sites, but is not a substitute for emissions cuts. Survival of outplants plummets under recurrent heat extremes; scaling to ecosystem level remains unrealistic without climate stabilisation. This perspective is consistent across the 2025 tipping‑points synthesis and multiple expert reviews (Global Tipping Points Report 2025; peer‑reviewed synthesis).

Maritime policy levers that work now

Treat the coast as critical infrastructure. Upgrade sewage treatment in reef‑adjacent towns and tourism hubs to secondary/tertiary standards; mandate nutrient load limits and real‑time turbidity monitoring for dredging and land reclamation near reefs. These measures are cost‑effective compared with disaster‑recovery spending.

Design MPAs for function, not only cover. Protect herbivore corridors and larval source reefs; enforce no‑take cores and seasonal closures keyed to bleaching forecasts.

Manage anchorage and traffic. Shift anchorage points to sandy patches away from coral heads; install permanent moorings at popular dive sites; incorporate reef‑sensitive routing in port approach charts.

Institutionalise heat‑stress early warning. Use NOAA and regional services to pre‑announce operational thresholds (e.g., temporary bans on reef walking, coral collection, or coastal construction when alerts hit predefined levels).

Plan for post‑bleaching recovery. Fund crown‑of‑thorns surveillance and rapid response; reduce herbivore harvest; phase restorations to follow cool seasons; monitor larval recruitment to adjust local closures.

Taken together, these actions do not solve warming, but they improve the odds that reefs can ride out shocks and recover, protecting coastal fisheries, tourism and natural breakwaters that reduce storm damage. The scientific consensus is clear: emissions cuts determine the ceiling, but coastal governance determines survival odds over the coming decade (NOAA; Global Tipping Points 2025).

Conclusion. The 2024–2025 heat years did not invent coral bleaching; they compressed time. In several provinces, the ecological tipping point where returning to prior structure and function becomes unlikely without long cool intervals appears crossed. Elsewhere, reefs still hold the line. Maritime authorities have leverage now: clean the water, protect herbivores, manage anchorages, and tie operations to heat‑stress alerts. These measures, paired with deep emissions cuts, are the practical path to keeping living reefs in the mid‑century seascape.